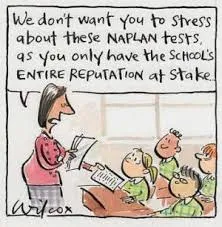

Since NAPLAN was introduced ten years

ago reading and numeracy have improved slightly and writing skills have gone

down and despite all the resources that have been invested in our system of

education we haven’t hit the lofty heights of excellence we were hoping for.

School performance in NAPLAN it is accepted, reflects best teaching practise so

teachers and students are under considerable pressure to perform.

NAPLAN

was the solution to a declared ‘crisis’ in education so we wouldn’t be ‘left

behind’ our international peers. Educational discourse centred on concepts of ‘failure’,

‘crisis’, ‘measurement’, ‘benchmarks’, ‘assessment’, ‘reporting’, ‘good/bad

teacher/student.’ Teacher’s professional worth was and continues to be

questioned and discussed in the public arena. What makes a ‘good’ teacher? If

teachers aren’t ‘good’ then are they ‘bad?’ ‘Bad’ teachers are the cause of

falling standards etc. Greg Thompson asserts in The International

Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives:

‘In Australia, one of the key

motivations for a national testing regime has been the various discourses

surrounding the “quality” of teachers in Australian schools, and a sense of some

real or imagined crisis impacting on Australian education.’

Continued and persistent focus on what

a ‘good’ teacher is and how can we lift ‘teacher capability’ to teach will

weigh heavily on the minds of teachers in every school and in every classroom.

An established regime of accountability has promoted what Susan

E. Noffke describes ‘a culture of performativity’ in education driven

by neo- liberal policies:

‘… the widespread influence of neo-liberal

policies which have resulted in a culture of ‘performativity’ (Ball, 2003). One

prominent example is the attempt to reduce the parameters of educational work

to doing only that which results in gains in the narrow band of standardised

achievement test, and the ‘mapping’ of curriculum and instructional strategies

against that which is tested.’

Teachers

are under pressure to perform according to set guidelines and this can be

confirmed in casual conversation with educators in any school setting. I won't

expand on the link between neo liberal policies and its effects but suffice it to

say I do believe that the work of the teacher is very much linked to an agenda

that is far removed from the classroom and the experience of the teacher and

learner in the school setting.

How

does this continued spotlight on the teacher effect general health and

wellbeing? I would like to consider this in the light of the REBT (Rational

Emotive Behaviour Therapy) counselling model. Albert Ellis’ ABC Theory of Emotional Disturbance

embodies the wisdom of many thinkers over the millennia e.g. The Stoic Philosophers,

Karen Horney, Alfred

Koryzybski and others.

The

ABC Theory is a philosophy based counselling model which posits that when something

happens (A) there is a behavioural and emotional consequence (C). The children

I work with often have an A=C philosophy which says ‘I am angry (C) because she

said I couldn’t join in (A)! Ellis said that how we feel and act at (C) can be

regulated by how we interpret/perceive/estimate what has happened at (A). This

part of the equation (B) alerts us to the cognitive component which drives the

strength of the emotion we feel and the kinds of behavioural choices we make.

|

| Dr Albert Ellis, creator of REBT |

In the counselling situation we want to help the student move form an A = C philosophy to an A x B = C philosophy or way of thinking. This helps the child/adult understand that he/she is an active agent in making feelings and choosing behaviours.

If

a person’s worth is challenged and questioned incessantly either explicitly or

by implication this can begin to unsettle a person’s view of self. This in turn

will affect how the person deals with difficult and challenging situations, the

(A) part of the equation.

Confidence

is an essential personal quality that is a buffer, a protective factor against

the adversities that we all inevitably are called on to deal with. It is

constructed over time and like a wall which is well constructed it will be

tested by all manner of assault and if it’s strong it will prevail. However

even the strongest of walls can be breached and compromised to the point of

failing.

What

is confidence? It’s a way of behaving, a projection of a certain sense of comfort

with oneself that allows for healthy risk taking to work towards set personal

and professional goals. She who feels confident will also deal with adversities

constructively. What we see behaviourally and emotionally and which we call

confidence is underwritten by an internal, deeply placed habit of

thinking/believing. It is what Ellis calls ‘unconditional self-acceptance’ a

steadfast belief that one cannot be defined by the opinion of others or how one

performs in a general sense. In other words someone’s idea about you does not and

cannot define the essence of who you are. Nor can failing at a task define you

as a failure. This is the ‘psychological wall’ of self-acceptance constructed

over time.

|

| Unconditional Self Acceptance - Albert Ellis |

However the foundations of this belief can be rattled under the weight of persistent judgement and appraisal based on ‘key performance indicators’ in a regime of testing and accountability which is so much the reality of the teaching and learning experience according to many.

Can

someone’s idea of self-worth be rearranged, reconfigured under such relentless

pressure? It seems this can be the case according to many who feel they are

performing to the beat of someone else’s drum. They do not feel in control,

they lack autonomy in what they do. Stephen

J Ball in The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity says that

the teacher is left to question her worth as a teacher experiencing:

‘…. guilt, uncertainty, instability and the emergence of a new

subjectivity. What Bernstein (2000: 1942) calls ‘mechanisms of introjection’

whereby ‘the identity finds its core in its place in an organisation of

knowledge and practice’ are here being threatened by or replaced by ‘mechanisms

of projection’, that is an ‘identity is a reflection of external contingencies’

(Bernstein 2000: 1942).’

I

regard this ‘new subjectivity’ to mean a shift in the foundation belief of

unconditional self-acceptance to a new and shaky assessment of self to be a

conditional one. This habit of thinking /believing i.e. ‘I am only OK if … my

kids perform well, if my line manager thinks I’m going OK, if the regional director

is happy with how the schools heading etc. Self-doubt may creep into her mind

about her ability to ‘be’ a ‘good’ teacher. What do her colleagues think of

her? Will she be asked to enter into some capability building exercise to bring

her up to standard? And how will others view this?

Albert

Ellis would say that the teacher has shifted from a position of strong self-worth

to one of conditional self-worth where she only feels validated when she meets

the expectations of a teaching regime that is laid out before her. What can she

do? She can challenge the status quo and articulate her concerns about how

things are going and how she feels about things. But how will this be received?

She may think that she will be regarded as ‘the problem’ and that she will have

to lift her game. She will have to lift her level of expertise to that of the ‘good,’

the ‘quality’ teacher. Is there a place for constructive criticism to be expressed

without fear of judgement? Is there a sense that what people have to say is valued?

Teacher

mental and overall health and well-being is challenged in the present climate

of teaching and learning. The culture of performativity can for some, undermine

their sense of confidence where their view of self is challenged because the system says they’re in effect no good!

In

conclusion concerns are held for personnel at every level who suffer under the weight

of the ‘reform solutions’ that have been determined for them in response to the

‘crisis’ we have in education. The

Conversation reminds us that:

‘Over

the past decade, the policy landscape has become riddled with reform

“solutions”. These subject students, teachers, administrators and policymakers

to mounting levels of pressure and stress. The short-term cyclical churn of

today’s politics and media clearly exacerbates these problems.’