The obsession with certainty in education is

perhaps a characteristic of our western way of life. We seem to want to know

without doubt that what we teach, how we teach it and how we measure its

efficacy is backed by the evidence. The evidence says that we should do this or

do that in schools and this is how it should be measured and reported on. These

imperatives are thrust upon a weary and disenchanted mob of educators whose

autonomy in the classroom has been surrendered to the experts and the evidence

they claim is true.

Pasi

Sahlberg who is the former director general of the Ministry of Education

and Culture in Finland and a visiting professor at the Harvard Graduate School

of Education, has been appointed professor of educational policy at

UNSW. He says:

“Maybe the key for Australia

is loosening up a little bit, less top down control and a bit more professional

autonomy for teachers.”

Mr Sahlberg on his travels in Oz is

reported to have said that he was broken hearted to see students in schools

buckling under the stress of high expectations, presenting with anxiety and

stress related crying and vomiting. This prompts me to consider how the school

curriculum itself and its reliance on testing and assessment puts undue stress

on the students who we claim ‘are at the centre of all we do’ is an antecedent

to mental ill health.

In his neck of the woods standardised

testing is almost universally rejected and there is more of a focus on play. Teachers

are required to have masters degrees and they maintain a high level of autonomy.

Students start school at seven years of age and may never be exposed to any

kind of assessment! Yet Finland when compared to other OECD countries based on

key education metrics including literacy and numeracy (Program for

International Student Assessment – PISA) is the strongest performer!

So what happens in the years before

students start formal schooling at the age of seven? There is a focus on health

and well-being and play is considered to be a natural way for young people to

learn how to relate to others, develop their problem solving capabilities and

to build and maintain positive mental health. All this without ever having been

tested on anything!

Kirsti

Lonka, Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Helsinki asserts:

‘Without creativity, a sense of wonder and play, none

of the great achievements in science or art would’ve been born. When we know

how to foster these skills in schools, our children have the best opportunities

to grow up to be happy and skilled people.’

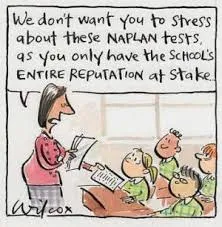

Meanwhile back in Australia students start

school at age five, and they are acculturated into the regime of NAPLAN,

ongoing assessment, competition and school league tables where schools are

focused on results and teachers are under too much control. Is it any wonder

that our students from the early years onwards are presenting with issues of

anxiety, depression and anger? Is it possible that the school is a risk factor

for the social, emotional and behavioural problems that children develop?

Since NAPLAN was introduced ten years ago

reading and numeracy have improved slightly and writing skills have gone down and

despite all the resources that have been invested in our system of education we

haven’t hit the lofty heights of excellence we were hoping for.

In New Zealand change is afoot as the new

Prime Minister moves to incorporate aspects of the Finland model into its

approach to education. The National Standards of Literacy and Numeracy has been

abolished for years one to eight and schools will choose their own way to

assess children’s progress, allowing educators more autonomy and control over

what they do. Minister Chris Hipkins says that schools will still collect a

range of data to track student performance but it will not go to a central

database to create school league tables (Labour's

education plans revealed). The aim is to focus more on learning and less on

excessive assessment.

There is a wide body of evidence that a

significant number of children experience a mental (ill) health condition. Educators

don’t need statistics to know this as they work daily with students who present

with a range of emotional and behavioural dispositions. A fair question would

be to ask if these conditions are caused and /or exacerbated by the imposed

learning and assessment regime. Sahlberg and his New Zealand counterparts

might agree with this proposition. Beyondblue

has published the following statistics to consider:

‘One in seven young Australians experience a mental

health condition. Breakdown: 13.9% children and adolescents aged 4-17 years

experienced a mental disorder between 2013-14, which is equivalent to an

estimated 560,000 Australian children and adolescents.’

If the hypothesis above has any credibility

then it may be asked; what is the function of mental health education and

promotion in schools? The answer is always that we want our students to be

happy and successful but perhaps educators and school counsellors might in part

be addressing the response of students to the stressors they experience in the

learning context. In this sense it could be the case that school is bad for

some kids because they have been introduced to formal learning too early and

they haven’t had enough time to build those foundation competencies and

attitudes that are conducive to long term success in a school setting; they’ve

had not enough time to play.

Michael McGowan in the

Guardian, Australia tells us:

‘Research has demonstrated that play in the early

stages of development can engage children in the process of learning and studies in New Zealand have found that

by age 11 there was no difference in reading ability between

students who began formal literacy instruction at age five or age seven.’

This is certainly food for thought for

those who drive and direct what schools do in Australia. Finland and New

Zealand educationalists would perhaps agree with Susan

E Noffke in “Revisiting

the Professional, Personal, and Political Dimensions of Action Research" who

comments on:

-

‘… the widespread influence of neo-liberal policies which have

resulted in a culture of ‘performativity’ (Ball, 2003). One prominent example

is the attempt to reduce the parameters of educational work to doing only that

which results in gains in the narrow band of standardised achievement test, and

the ‘mapping’ of curriculum and instructional strategies against that which is

tested.’ P.18

|

| Susan E Noffke |

‘NAPLAN preparation is taking up a lot of time in a

crowded curriculum, that there are other curriculum areas that are seen as not

as important because they’re not tested. That they teach more to the test, so

they make sure that they cover the knowledge that’s on the test, and that means

that they’re not teaching other things.’

This was 2012 and one wonders if anything

has changed? But we persist in our schools to put a heavy premium on assessment

and though unintended the outcomes are plain to see. Perhaps the winds of

change are gathering momentum. The Finnish and New Zealand experiences are

wafting on a breeze of hope for the future.

Comments

Post a Comment